This reflection explores how coaching young people isn’t just about football—it’s about building safer, stronger communities through care, consistency, and connection.

A few years ago, I wrote a short reflection on why people coach while I was with United Glasgow. At the time, it was based on years of experience in schools and grassroots setups—from Erskine to Maine (USA), Mallaig to Doha, working with refugees and now young folk in Drumchapel. Since then, I’ve taken on new coaching roles, completed my UEFA C Part 1 and 2, and found myself more convinced than ever that football—particularly youth football—is far more than just a game.

It’s a public service. An overlooked one.

Working with Renfrew Ladies and now in Drumchapel, I’ve seen the power of football to connect communities, foster belonging, and teach young people lessons that many of us must learn.

But I’ve also seen how undervalued these spaces are—especially when it comes to the so-called “soft” skills that are anything but soft: emotional intelligence, trust-building, vulnerability, feedback, and resilience.

So, this post is about that. Coaching as community work. As education. As protection. And as one of the most accessible tools, we’ve got to nurture future generations—on and off the pitch. It was writing for my UEFA C submission that got me thinking about this and inspired me to write this post.

Well-being and Protection: It Starts with Trust

One of the biggest takeaways from the Scottish FA Well-being & Protection in Youth Football course was simple but powerful: safeguarding isn’t a checklist. It’s a culture.

Every session, I greet my players by name and check in about school, family, and anything that matters. These aren’t performative rituals; they’re a foundation for emotional safety. Because here’s the truth: children can’t learn, engage, or enjoy anything if they don’t feel safe. If they’re scanning the room for threats—emotional or physical—they’re not taking on new ideas or building confidence.

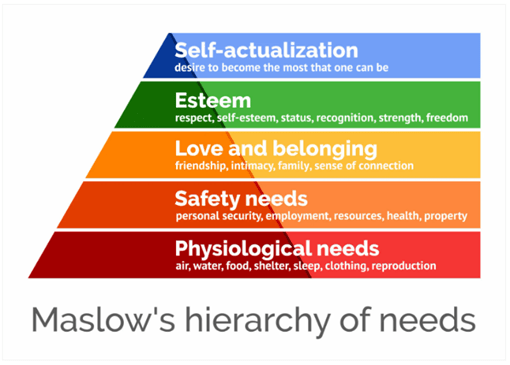

This mirrors what I saw in Scottish classrooms. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs isn’t just theory—it’s felt. Without safety and belonging, learning stalls.

That’s why I insist on working with parents, carers, and guardians as key partners. The best sessions are when communication continues beyond the pitch, and families feel heard and supported. It reinforces consistency, trust, and care across the whole environment.

Collaborative Learning, Football-Style

My teaching career and current job have always leaned on collaboration. Whether it was peer marking in higher classes, group problem-solving with S1s, or doing some visual root analysis with engineers, I know people learned more when they were active contributors—not passive recipients.

That’s how I coach now. I’m aggressively transparent and want to share training materials with players, parents, guardians, and other coaches.

This mindset is built on my experience that giving people tools and background knowledge will help them drive their learning and development. It is also a personal whiplash, from the “knowledge is power” cliché, as coaching and managing shouldn’t be about power, but collaboration and co-operation to solve problems, develop and get things done.

In football, teaching young people the hows and whys might take more time in the beginning. Still, I’ve learned that it leads to players taking the reins in their own warm-up mini-games, leading sessions, and reflecting at the end of sessions on what went well. We co-create our space. And the feedback loop isn’t just from coach to player—it goes both ways.

This approach transforms training into a collaborative, student-led environment. It aligns with the tools and methods I saw thrive in schools—especially when learners feel seen and respected.

Growth Mindset and the Power of “Not Yet”

The UEFA C Psychology module by Steven Sallis hammered home the importance of mindset. A lot of the discussion echoes what I learned in teaching and business with Jacobs. My older senior managers and mentors would really push that to get the best out of folk, and getting people who are developing to move away from thinking, “I failed” to “I haven’t mastered it yet” is huge.

This mindset has also led me to tell other coaches and parents, that players have nothing to prove other than they want to improve. Even professionally, I struggle to work with people who are not curious and tell me, “This is how it has always been done,” despite obvious flaws and issues, and who don’t push and support staff to develop and grow.

So, back to football, in my U14s team, I frame mistakes as stepping stones. A misplaced pass? It’s not a failure; it’s a brave decision to try something challenging. That shift—from fear to curiosity—is the foundation of a growth mindset.

I model this, too. I’ll admit when I don’t get something right and ask the players how we could improve it together. I want them to see that progress is messy but worth it.

Emotional Regulation: Box It, Bin It, Move On

Another reminder I got on the course was about visualising emotions, putting them in a box, and bin it. I was lucky to grow up with supportive uncles. One is an alcoholic who has been sober for over 30 years, and another is a former social worker. Having these two strong characters in my life helped to guide me in managing emotions and having empathy and compassion for others.

This anchored my mindset to support young people and pass that on. Teenagers feel everything. They are a constant emotional rollercoaster, and a training session can derail very quickly without the coaching of resilience. The “Box and Bin” technique, I can’t stress enough, in getting people to take the time and have patience with themselves and others has the power to be transformational.

How does it look on the pitch? After a mistake or a goal is conceded, we “box” the emotion, acknowledge it, then “bin” it, and get back to the action. It helps players stay present and stops them from spiralling.

It’s a strategy straight out of the classroom: practical, accessible emotional literacy. And just like in teaching, I’ve learned that if you can help people name their emotions, they’ll be far better at managing them.

So the chimp paradox video below gives a good explainer to help folk understand some fundamentals of emotional regulation.

Safeguarding Through Consistency and Culture

Safeguarding is not just a checklist of rules; it’s a lived culture of consistency, professionalism, and care that shapes how safe young people feel, not just how safe they are.

For example, I’ve made it a non-negotiable never to be in one-on-one situations. I follow safeguarding protocols and best practices to the letter and maintain open, ongoing relationships with families and carers. However, these measures are only as effective as the culture within which they sit.

Rules can protect in theory, but what young people notice—and respond to—is the consistency of adult behaviour. When everyone in the team walks the walk, holds boundaries, and communicates with friendliness and respect, that’s when players genuinely feel safe. They begin to absorb those same values in how they treat each other and navigate the world.

In community sports and youth work, it’s easy to fall into the trap of relying on policy documents alone. But it’s the everyday stuff—the tone we set, the way we show up, the trust we build—that truly safeguards.

We must ask: “Does this feel safe, fair, and supportive for everyone involved?” Because when safeguarding becomes part of your culture, not just your compliance, that’s when it works.

Coaching as Social Infrastructure

Coaching isn’t just about sport—it’s a vital form of social infrastructure. It offers one of the few remaining spaces where people from different backgrounds and generations come together with a shared purpose.

Think about what gets learned on the pitch: confidence, resilience, teamwork, emotional control. These aren’t just football skills—they’re life skills. I’ve seen young players who struggle in the classroom thrive when given structure, care, and responsibility through sport.

In that sense, coaching is a form of education. But for it to work, it needs the same foundation—predictable structure, consistent care, and emotional safety. The best sessions aren’t just well-drilled; they’re well-held. Young people learn because they feel secure, seen, and supported.

We should be talking about coaching as community building. As youth services get cut and schools are stretched, football clubs quietly do the heavy lifting in social development.

Let’s stop ignoring the value of these clubs, from Drumchapel, North Kelvin, Erskine, and Renfrew(some of the clubs I have had the privilege of coaching with). These clubs, if anything, are a must-have—because coaching, done right, can be a powerful tool in shaping the kind of adults our communities need.

Final Thoughts: The Game Behind the Game

Youth football isn’t just weekend matches and training. It’s a long-term investment in confidence, character, and community.

And yet, the skills required to deliver that—coaching, safeguarding, reflection, relationship-building—are still underappreciated in the public realm.

My closing argument: if you’ve ever played, supported, or coached—look again. You’re not just part of a team. You’re part of our social fabric. Let’s recognise coaching and those who support our community clubs for what it really is: it’s not just about sport but about shaping stronger, safer, fairer communities that value people and help people be the best version of themselves.

So, to sign off, some happy memories from the past couple of seasons.

Leave a comment